Fragility fractures are associated with high rates of disability, loss of independence, reduced quality of life for both patients and their carers, not to mention significant costs to healthcare systems.1 Despite the high associated morbidity and mortality, osteoporosis remains under-diagnosed and under-treated.2 Those who experience a fragility fracture are at high risk of re-fracture.

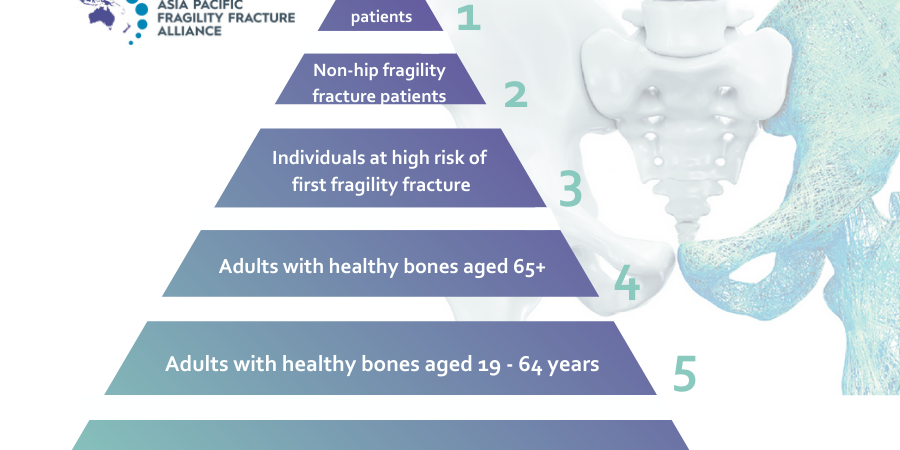

Post-fracture care (PFC) programs are systematic, coordinated care programs that identify, evaluate, and manage patients who have sustained a fragility fracture, with the goal of preventing further fractures. PFC programs exist in many forms, with the two main models being outpatient fracture liaison services (FLSs) and inpatient geriatric/orthogeriatric services (OGSs).3

In an Osteoporosis International review titled Post-fracture care programs for prevention of subsequent fragility fractures: a literature assessment of current trends, published March 24, 2022, the authors strive to understand trends in publications about PFC programs over the years; evaluate key characteristics of FLSs and OGSs; assess clinical effectiveness, geographic variations, and cost-effectiveness of PFC programs; and identify barriers and solutions to implementation of PFC programs.4

The authors explain their search for peer-reviewed articles resulted in 784 articles with relevance to PFC programs published between January 2003 and December 2020. During this period there was an increasing awareness of the importance of PFC programs in overall patient care, with the number of PFC-related publications increasing annually. Nonetheless, a publication gap remains in several countries, including those countries with a reported high incidence of fragility and/or hip fractures. This is likely impacted by geography and socioeconomic status, although further research is required to provide further information on the topic, according to the review’s authors.4

The benefits of FLS and OGS programs are well documented. Notably, combining FLS and OGS approaches together with the development of fragility fracture registries to provide ongoing research to advance key performance indicators (KPIs), could improve the effectiveness of PFC programs the most. Combining FLS and OGS approaches appears to result in approximately 2- to 5-times improvement in outcome measures, such as program enrolment, osteoporosis testing and diagnosis, and initiation of osteoporosis therapy.[5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]

It appears there is a trend toward the treatment of elderly patients, and in the diagnosis and treatment of vertebral fractures.14Articles on orthogeriatric and hip fracture care still have a stronger focus on survival and comorbidities, rather than on re-fracture rates.

As is known, patient adherence to osteoporosis medications varies, with interventions that include prescribing osteoporosis medications, often showing improved patient outcomes, but not at optimal levels. Inconsistent reporting of quality improvement measures is still a key challenge, but there is now evidence of some efforts at harmonising quality improvement measures for PFC programs,[15,16,17,18,19] the review’s authors maintain.

The further success of PFC programs includes the implementation of registries, educational programs, and continuous updates of osteoporosis guidance for HCPs. The US registry AOA’s ‘Own the Bone®’ program15 defines quality improvement measures and is credited with successfully improving the behaviours of medical professionals about osteoporosis treatment and managing patients. An independent registry20 showed an increase in identification of patients with fractures who are ≥ 50 years from 0 to 74.5% as a result of registry implementation, with 33.9% of those identified patients proceeding to undergo screenings and follow-up visits. In addition, the world-first APFFA and Frailty Fracture Network, Hip Fracture Registry (HFR) Toolbox21 provides a distillation of information from existing national registries and practical advice on starting new registries. The Toolbox aims to advocate for, and support clinicians, hospital administrators, healthcare systems and governments with, establishing a national registry in their respective countries. For educational programs, the US-based Bone Health Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (TeleECHO) uses video conferencing technology, and represents a model that could be replicated to include the education of FLS coordinators and other HCPs to expand the pool of specialists who can provide bone healthcare to patients.22 Several organisations worldwide are now hosting Bone Health TeleECHO programs, including the Bone Health and Osteoporosis Foundation (BHOF) and the American Orthopaedic Association (AOA).

Lessons learned during the COVID-19 pandemic and implementing PFC delivery should include increased use of telemedicine and virtual technology, especially in rural and remote areas, according to the review’s authors.

Geographic variation-wise, PFC programs continue to expand in new and under-served regions and countries, and in countries with established PFC programs. The trend seems to be toward OGS programs. However, there is still a care gap, with issues of consideration, such as the impact of healthcare system types, and proximity to clinics or healthcare facilities, especially in countries with less developed healthcare infrastructure.

PFC programs are cost-effective,[23,24,25] with high-intensity interventions, such as Type A FLSs, being more expensive, but generally cost-effective, or even cost-saving.[10,26] There is evidence that reimbursement may be a bigger driver of funding decisions than quality of care.[25,27]

The review’s authors are concerned there is still “inconsistent reporting” of economic outcomes. Not all studies report incremental cost-effectiveness ratios or quality-adjusted life-years (QALY), and “it may be more helpful to focus on cost or cost savings per patient,” they maintain. In assessing the economic cost of subsequent fragility fractures, the authors reflect that “most articles do not factor in indirect costs, such as lost productivity, even though these costs are generally considered substantial”. Lack of information is “the main barrier to prevention of subsequent fracture”, which they assert, can be addressed by educating population healthcare decision-makers, HCPs, and patients to understand the personal and societal burden of osteoporosis.

To read the full article, click here.